WHAT CHINESE INTERNET CENSORSHIP LOOKS LIKE “ON THE GROUND” AND HOW IT AFFECTS DEMONSTRATIONS MARKING THE 25th ANNIVERSARY OF THE TIANANMEN SQUARE MASSACRE

by Kinzy Janssen

A version of this post was originally published in Volume One Magazine.

When I was young, I had no idea Tiananmen Square was a place. It was something that happened–a man that faced down a line of tanks. People don’t say “Do you remember what happened at Tiananmen Square?” They just say, “Do you remember Tiananmen Square?” The place is synonymous with violent government oppression.

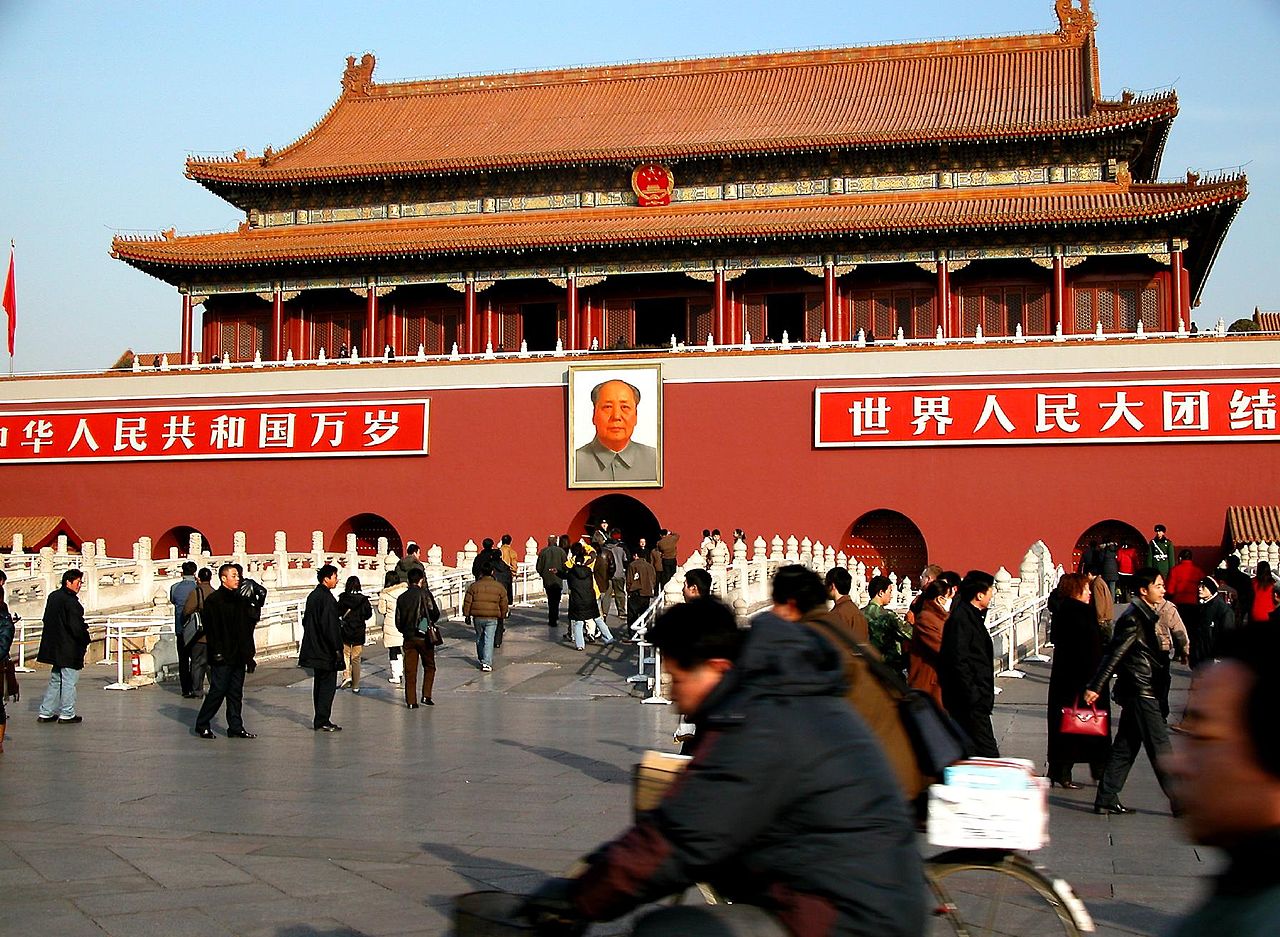

In 2011, when I stood on the 109-acre concrete expanse that is Tiananmen Square, my whole body was more attune to (and more reverent of) those students’ deaths in 1989 than the hundreds of years of ancient history beneath my feet. I found myself squinting at the pavement, looking for faint signs of bloodshed, but it was immaculate. This woozy feeling of closeness—of solidarity—is an important one. Today, on the 25th anniversary of the violent crackdown on pro-democracy protests in Beijing, it’s more relevant than ever.

///

When I taught ESL in Shenyang, China, I often conducted one-to-one classes, spending eight hours a week with one adult student in a tiny classroom. We faced each other in furniture made for five-year-olds. My role was conversationalist more than teacher, and our topics drifted far and wide, from the NBA and American weddings to whether or not I could cook/drive/haggle in China. I never brought up politics, but sometimes they did.

“What do you think of the Chinese government?” a student named Manny asked.

His eyes were hard to read, and my eyes wandered to the upper corners of the classroom, half-expecting a spy to suddenly materialize, Spiderman-style. I answered slowly, admitting my suspicion of shoddy workmanship on government projects such as elementary schools and bridges. But this was the green light Manny had been waiting for; he spoke frankly about the helplessness his fellow citizens felt toward the regime. He spoke in superlatives. Apparently, no one believed their government to be healthy, and everyone discussed these matters in the safety of their own tightly knit circles. To act on their feelings would be to risk house arrest, or worse. Manny’s tone was bitter – how could an American understand this climate of silence?

Though living in a foreign country for a year constitutes a role somewhere between resident and tourist, I experienced this climate of silence almost daily through Internet censorship. You’re probably aware of China’s tepid relationship with Google, but here’s what that looks like on the ground: After an arbitrary number of searches (three? five? ten?) the server would time out, shutting down my laughably innocent image searches for “cow” or “tree,” intended only for homemade flashcards. It is one thing to hear about China’s Great Firewall in theory, but it is another to see the error message pop up at your fingertips: “Sorry. The server has timed out.”

It was no coincidence, however, that a few, select search items always timed out, those being “Arab Spring”, “Tibet” and “Tiananmen Square.” Sadly, many of my students believed Google to be a faulty (and thus inferior) search engine compared to China’s BaiDu. They didn’t realize the government was manipulating those glitches. They didn’t see the puppet strings. (Once, however, a particularly bright student told me the reason he wanted to go to the U.S. was to read “real” history books for the first time).

From my students, I learned that it is only possible to access the Internet by first plugging in the equivalent of a social security number. In order to access Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube while in China, I had to enlist the help of a tech-savvy friend to create a proxy server for me in the States—basically a way to skirt censors by signing on to an entirely different server. To get to Facebook, I had to go to Pennsylvania first. This was a luxury. I never learned (never wanted to learn) whether rerouting was illegal, but I felt protected in my status as an American citizen.

Now, but especially on today’s anniversary, Chinese citizens are relying on delicate nuance and euphemism to openly and collectively address sensitive issues. As government censors and police work overtime today, LA Times reporter Barbara Demick says citizens are representing the date (6/4) by using mathematical equations (63+1). One activist-photographer used eight playing cards arranged cleverly to spell out the date (8964) and refer to weaponry (AK47). To me, the most poignant protest Demick describes is the one where citizens plan to sing “Do You Hear the People Sing?” of Les Miserables at Tiananmen. Some will only hum, but all will risk arrest.

///

It is important to stand in solidarity with the Chinese today for their sake and our own. Our causes are not separate.

In March of 2011, I was sitting in the teacher’s lab in Shenyang, browsing BBC news online when I did a double take. There was an article depicting the Wisconsin state capitol (my capitol!) filling with thousands of people and hand-painted signs. The protests, which raged for weeks, were an angry response to Governor Scott Walker’s strike-down of a union’s right to collectively bargain. At the time, I was immediately proud. In fact, the reality of that distance – six thousand miles – suddenly magnified the power of a democracy against the cultural backdrop of China.

Now, three years later, there are new laws that address, of all things, singing in the Wisconsin state capitol building. Groups of 20 or more people may not sing inside those walls without getting arrested. But, like the Chinese, they do it anyway. Freedom of speech is something that is constantly in flux.

Today, if you Google “Tiananmen Square” and see “Tank Man” pop up, don’t take that for granted.