A cast of delinquent characters and a gritty setting sheds light on social politics in this modern fairy tale.

by Joanna Demkiewicz

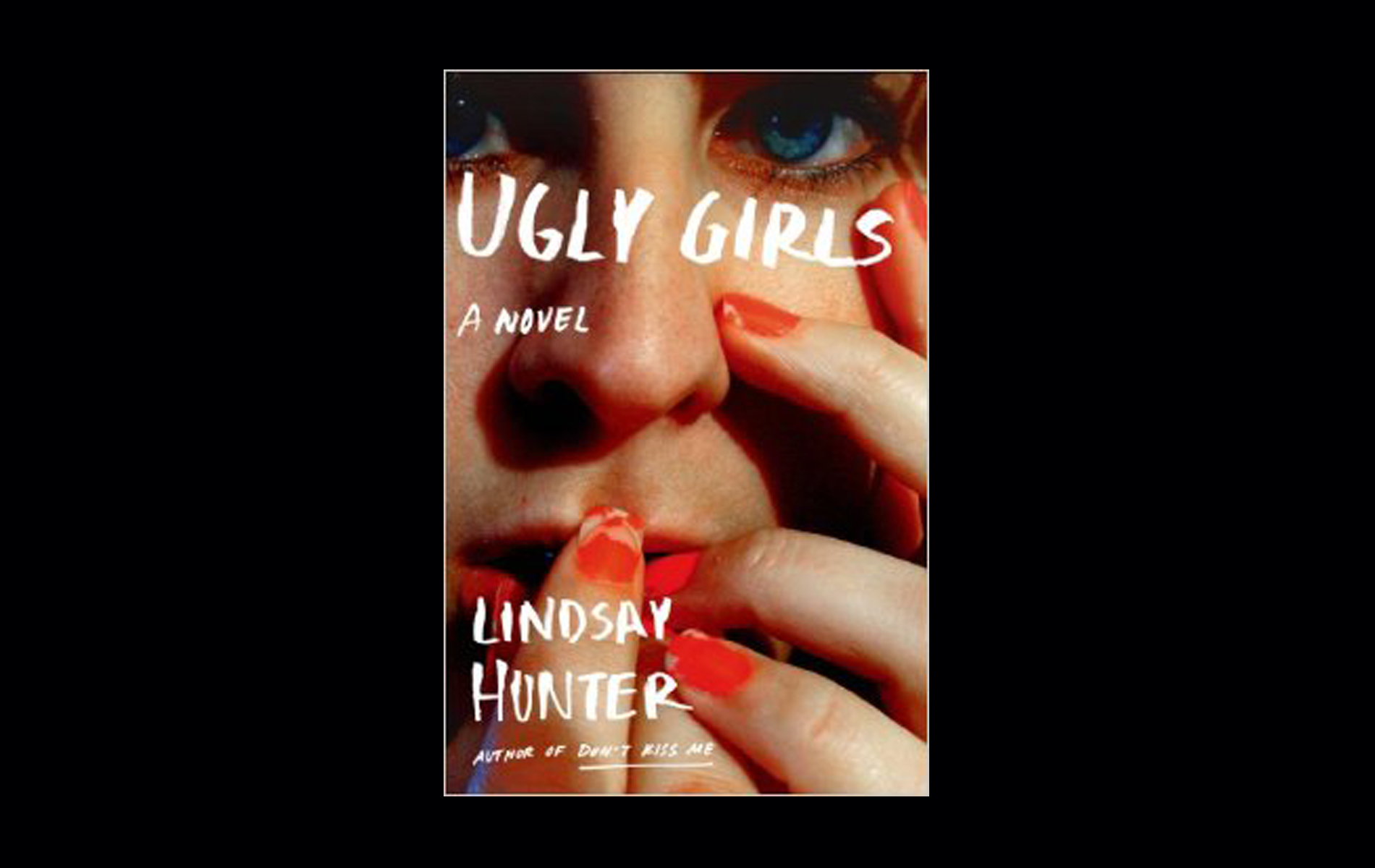

Lindsay Hunter has reimagined the fairy tale. Ugly Girls, out November 4, is reminiscent of a Grimm’s fairy tale but so approachable and contemporary that you are terrified because you know these characters. They are the cashier at Walgreens, the ice cream scooper, the security guard, your friend, you.

Hunter’s first novel is about two ugly girls, Baby Girl and Perry–either ugly on the outside, inside or both–and the constant power struggle between them. In its realism, it is a nightmare; I’ve been telling people it’s a “thriller”. The story is as visceral and stomach-churning as the Queen’s cruel pursuit in poisoning Snow White. As Baby Girl would say, ‘I’ma get mine,’ and I think she would identify more with the Queen than Snow White in her prowl for control.

Baby Girl and Perry are high-schoolers living in a bland trailer park, a place where everyone is so close that the TV glow from a neighbor’s trailer is as constant as a streetlamp, a place so lacking in privacy that the only place to go is away. The reality, though, is that Baby Girl and Perry don’t have the resources to really go away. They disappear at night to steal cars and break into houses nestled in the Estates. They’re only destructive when they dare each other to be, and sometimes they don’t challenge one another. That’s when they just steal gold napkin rings. Then they go home.

Perry lives with her alcoholic mother, Myra, a woman who decided to raise her daughter the opposite of how she was raised, which means she is hardly present, thinking she’s doing her daughter a favor. Perry’s saving grace is her stepfather, Jim, who works as a security guard at the local prison. He spends the night shift patrolling desperate, incarcerated men, then drives home to pick Perry up and then drop her off at school.

Baby Girl is the new “man” of her house, after her older brother, Charles, suffers brain damage from an accident. She takes this position seriously and seeks to embody the Charles she used to know and revere. She shaves her head and wears his clothes. She buries her old self in the new thug persona. No one gets to see her weak: “Baby Girl wanted her outside to look like how she felt on the inside. Which was Fuck you.”

The entire novel is a gun cock. Each chapter, which switches from Baby Girl to Perry to Myra to Jim to the predator who lives in the neighborhood, pushes the bullet further through the barrel. Hunter’s previous books, Daddy’s and Don’t Kiss Me, are flash fiction stories–and practically every sentence matters. “The night was warm as a mouth,” Perry says while cruising with Baby Girl in a stolen car. These characters might do bad things, but Hunter gives them intuitive, observant voices so intoxicating you realize how easy it is to care about someone unlikable.

Most impressively, Hunter manages to open the door to social politics in just 229 pages: This book is not only about “ugliness”, friendship and perception, but also about class, desire, sexuality and the power dynamics between men and women. The predator who lives in the neighborhood uses Facebook to lure Baby Girl and Perry to him, and as two girls who have never been handed anything, they know they have to be the ones to take control. Good judgment can be blurred by the constant pressure to appear stronger than a social crutch.

As with all Grimm’s fairy tales, this story is not suitable for children. It is at once dark and charming, but this time it’s 2014, and the hardest thing to shake is that these characters, while fictional, are real.

[hr style=”striped”]

Joanna Demkiewicz is The Riveter‘s co-founder and co-editor. Find her on Twitter at @yanna_dem.