Journalist Mac McClelland’s second book gives a new face to PTSD—her own.

by Kaylen Ralph

This week, ex-Marine Eddie Ray Routh was officially charged with the 2013 murder of U.S. Navy Seal Chris Kyle (as portrayed by Bradley Cooper in American Sniper). American Sniper’s box office success resulted in a heightened awareness both for the case, and for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Routh’s lawyers argued with a defense that hinged on “convince(ing) jurors that Routh was schizophrenic, suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder, and was in the midst of a psychotic episode” when he shot and killed Kyle (and another person) at a Texas shooting range in 2013.

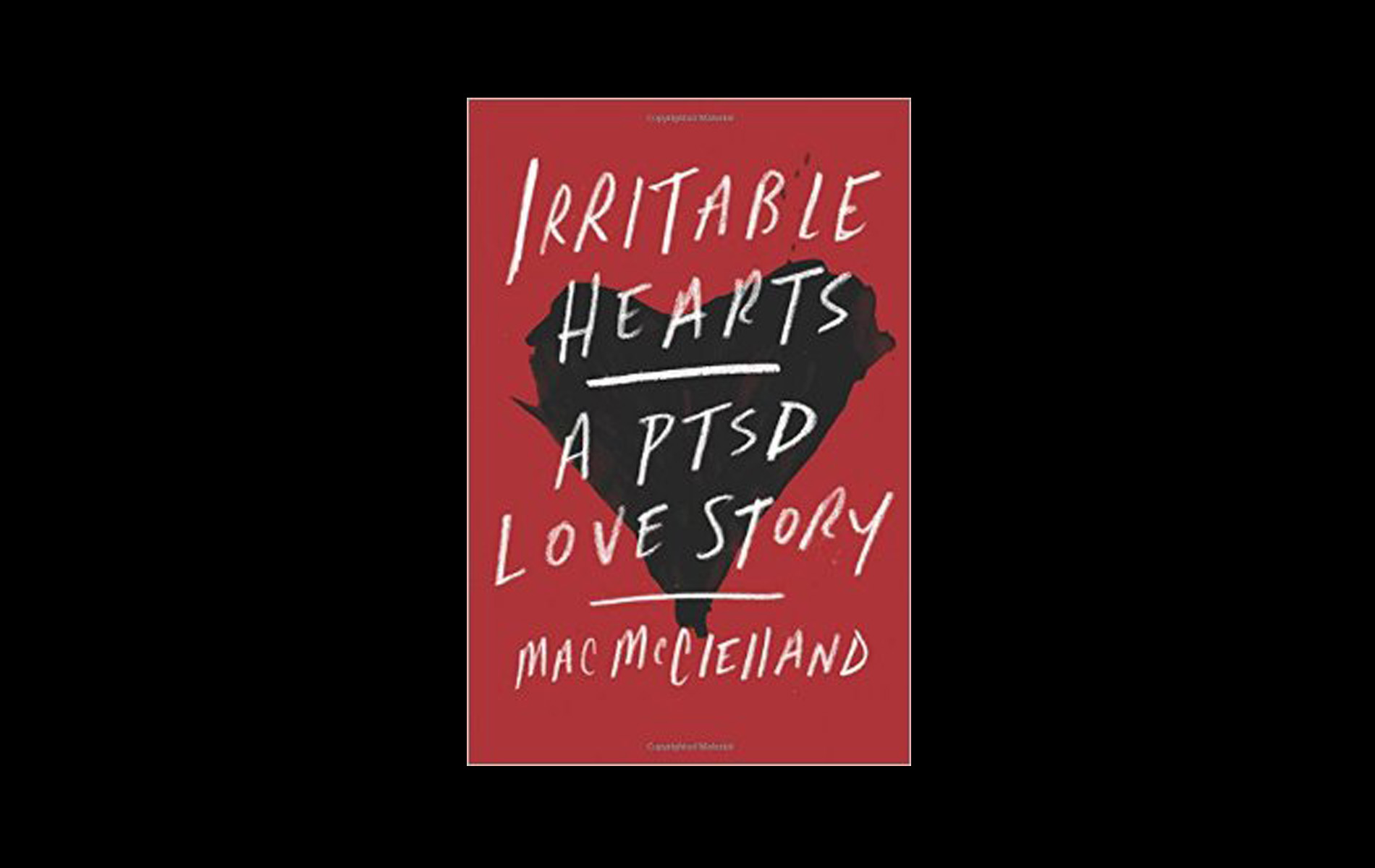

Without commenting on the case, specifically, I think it’s interesting and notable that it took the jury less than three hours to arrive at their guilty verdict, especially after reading Mac McClelland’s Irritable Hearts: A PTSD Love Story, also released this week, which recounts McClelland’s experience battling PTSD, triggered while reporting in Haiti after the earthquake in early 2010. As in the case of Routh and Kyle, there is a lot of controversy surrounding McClelland. I think Irritable Heart’s release comes at a perfect time, though, as many people still associate PTSD with veterans almost exclusively. McClelland is not a veteran, she’s a human right journalist, but when she “came out” in 2011 as a reporter suffering from PTSD, the media didn’t hesitate to berate her for “carelessly exploiting” a Haitian rape victim in the interest of getting her own PTSD story out into the world (while reporting in Haiti, she witnessed a rape victim encounter her attacker). She writes in Irritable Hearts: “When I had written the offending piece, I had considered that morning when we were in the same place a story that belonged to me, too, because the rest of my existence had hinged on it…In any case, when I said No, I wanted people to respect that without qualification and no questions asked. And I had failed to do that for her. I hadn’t been able to figure out a way to disconnect us, a way both to own my own trauma and do that for her. It would remain my strongest and most convincing point of self-disgust for a very long time.”

But Haiti post-earthquake was a desperate place, as is any region after a massive natural disaster. That McClelland’s own trauma was intertwined with that of Haitians indigenous to the land is inevitable. McClelland herself was never raped, but widespread sexual harassment and violence dominated much of the discourse following the earthquake. She was reporting on it while experiencing it.

McClelland got her start as a human rights journalist after reporting on the Burmese refugee crisis in 2006, the result of an ethnic minority fleeing in the face of state-sponsored genocide. She wrote an entire book about this tragedy in 2010. What followed, career-wise, was a series of back-to-back assignments in intense, combative locations—New Orleans post Hurricane Katrina (where McClelland actually lived during the time); the Gulf Coast after the oil spill, where she was “unable to stop a weepy fit from coming on after a white oil-spill cleanup worker told (her) to notify him if any black cleanup workers hit on (her), so that he could organize a lynching;” and Native American territory, where a “vigilante economy thrived” and she was subjected to sexual harassment from sources.

A journalist’s role is to observe and report, but doing so from within the mental prison of a disease such as PTSD can seem impossible. That’s why McClelland’s inclusion of Nico, McClelland’s husband (a French soldier whom she meets almost immediately upon arriving in Haiti), is so important. Though she struggles to grasp what’s happening to her, she’s able to describe in great, moving detail how Nico reacts to her “episodes.”

At times, Irritable Hearts feels like a meticulously detailed diary of professional horrors. This only enhances its value both as a memoir and resource in the pursuit of a better collective understanding of this condition. As McClelland writes, “At least 25 percent of Americans have experienced a trauma by the time they reach adulthood, and by the age of forty-five, almost all of them have.” Obviously not all instances of exposure lead to PTSD, but this fact alone (and the countless others McClelland braids in with her personal experience grappling with the disease), elevates her memoir to something even more important—a roadmap, a manifesto, a call to action.

[hr style=”striped”]

Kaylen is one of The Riveter’s co-founders and the EIC. She moved to Minneapolis, MN after graduating from the Missouri School of Journalism in August 2013. In addition to her editorial duties at The Riveter, Kaylen also works as a freelance researcher for The Sager Group. You can follow her on Instagram and Twitter at @kaylenralph.