As survivors of Hiroshima start to age, they keep their stories alive through passing them down to younger generations.

Photos and reporting by Amanda Solliday

In a house located near the center of a bright, modern Japanese city, 82-year-old Kiyomi Kohno sits around a low table with her daughter, Nobuko Morikawa.

As Kiyomi speaks in Japanese, her daughter provides an English translation.

“Hello everyone; welcome to Hiroshima.”

The story begins with scorched land followed by deadly rain. Kiyomi lifts her sleeve to show the scars on her arm, faded slashes on her skin that serve as a constant reminder of the last days of World War II. For more than an hour, Kiyomi describes her life as a hibakusha, a survivor of the atomic bomb.

Kiyomi traveled to America to share her story four years ago, and that’s when her daughter Nobuko, at the age of 53, first began translating for her mother. Nobuko said she feels that the experience of the bomb is an important part of her family’s narrative.

“I want to continue telling my mother’s story,” Nobuko says. “And my daughter is interested in her story. She always listened to the story when she was a child.”

Now, nearly 70 years after the Aug. 6, 1945 bombing, even the youngest atomic bomb survivors are elderly. Many aging atomic bomb survivors are leaving their legacy with their families, community and any outsiders willing to listen, with hope that their stories will prevent future use of nuclear weapons.

///

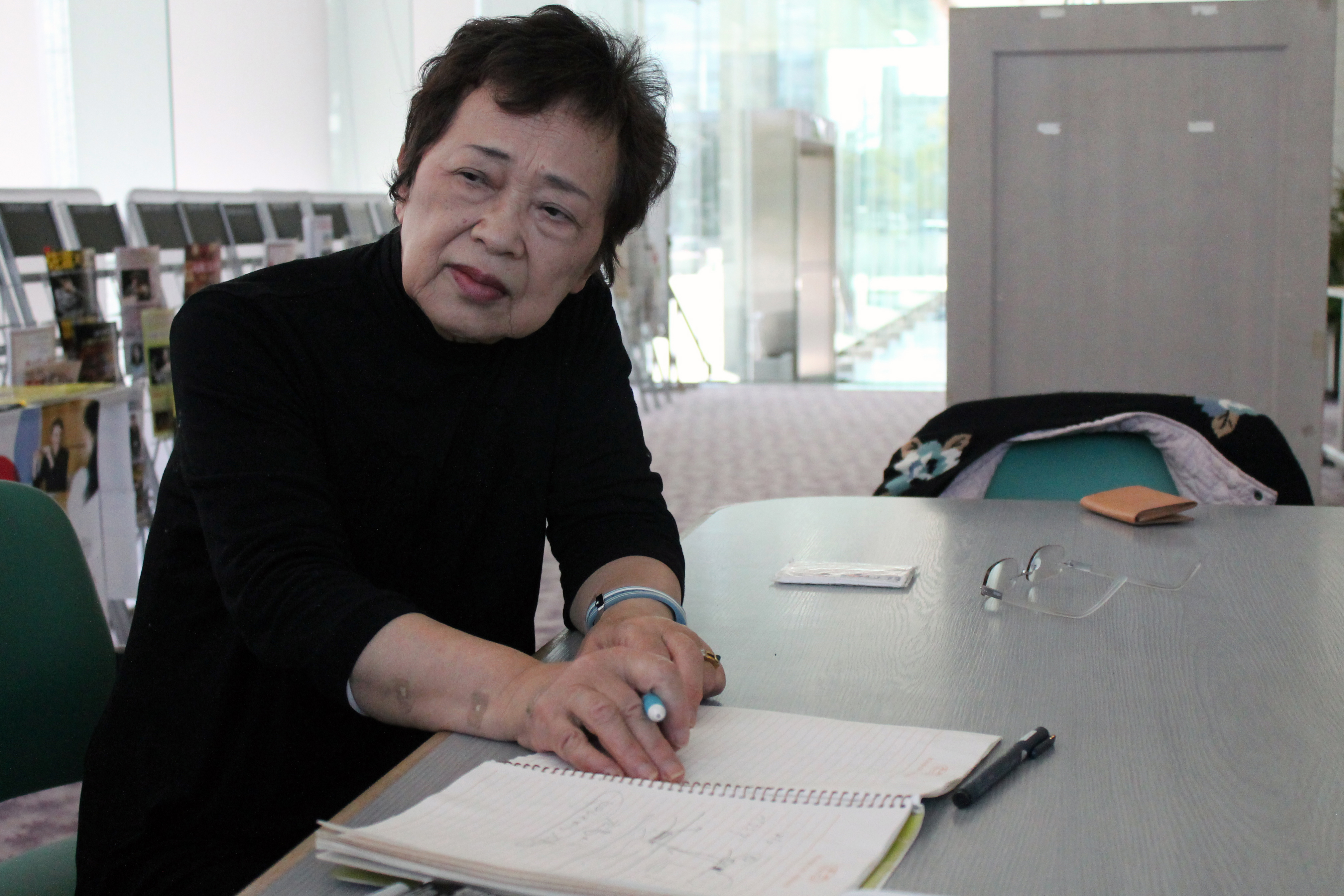

Setsuko Enya – a fellow bomb survivor and grandmother – also wants her family and others to understand what happens during nuclear war. Setsuko (pictured above drawing a diagram of ground zero in Hiroshima) was five years old in August 1945, but she still remembers the destruction inside her house on a hill located just around a mile from where the first atomic bomb struck Japan.

“Suddenly the roof of the house collapsed. I was trapped in the debris and darkness. I saw light above, and my mother’s powerful hand reached me,” Setsuko says. “My mother also rescued my grandmother and my younger sister.”

Though people could talk about these types of bombing experiences among families and friends, wider discussion in Japan was banned. After World War II, the U.S. occupying forces initiated a strict press code, preventing Japanese citizens from discussing the atomic bomb with the media or sharing images of the aftermath.

“We had no freedom to talk about the A-bomb and the A-bomb disease,” Setsuko says. “They censored publications, books and everything.”

Jim Boland, director of the Peace Resource Center at Wilmington College, says that this censorship kept Japanese citizens from knowing what actually happened in Hiroshima.

“People knew about the bomb in the abstract, but the details were suppressed and kept out of the public eye,” Boland says.

We had no freedom to talk about the A-bomb and the A-bomb disease.

Long after the press code was lifted, Setsuko still hesitated to tell her story because she felt her contributions did not matter, as she was so young when the bomb hit.

Eventually, though, Setsuko decided to speak.

After the bombing, Setsuko experienced acute radiation effects, including bleeding gums, hair loss, purple spots on her skin and exhaustion. Her sister was one year old when exposed to the atomic bomb, and she died of complications due to radiation exposure seven years later.

“We were in the same situation, both of us in the house,” Setsuko says. “But I don’t know why Estu-chan died.”

The memory of her sister and other innocent children who died encouraged Setsuko to tell her story.

“They had a bright future,” Setsuko says of the youngest victims, “but their life was lost suddenly.”

A few years ago, Setsuko was featured in the Japanese Broadcasting Corporation (NHK) documentary “From Hiroshima to Hiroshima” – a film her small grandson, a frequent watcher, calls “Grandma and the Atomic Bomb.” Setsuko’s story, like Kohno’s, has become a family affair.

“Even now, I feel as if my mother is pushing my back, encouraging me to tell my A-bomb experiences,” she writes in a personal essay.

///

Another survivor, Emiko Okada, was eight years old and at home the morning the bomb struck. One of her strongest memories is the limited availability of medicine in the city after the bombing. She says there were few resources to help survivors with all the injuries and sickness.

“No hospitals, doctors, nurses, no medicine at all. In the scorched land, we found exposed, white bones and ground them into powder to put on burns,” Emiko says. “Human bones.”

Such memories can be excruciating for today’s survivors. At a young age, they suffered severe injuries, watched their loved ones and friends crushed or incinerated, and saw destruction on a citywide scale.

“All A-bomb survivors felt the fear, the horror, the pain and the sadness,” Kiyomi Kohno says.

‘In the scorched land, we found exposed, white bones and ground them into powder to put on burns,’ Emiko says. ‘Human bones.’

For years after, they suffered physical and emotional pain. The stories are decades old, but many survivors choose not to endure the stress of retelling their experience. Rehashing the old stories can reopen old wounds.

Bo Jacobs, an international studies professor at Hiroshima City University who specializes in the cultural history of nuclear weapons, says only a minority of survivors have ever described their experience publicly. Although the actual numbers are uncertain, the local peace community in Hiroshima estimates that only around 10 percent of survivors ever speak publicly about the bomb, Jacobs says.

Only around 10 percent of survivors ever speak publicly about the bomb.

Beyond the terror of the explosion, the lasting emotional legacy corresponds to fears of a medical heritage due to radiation exposure.

The most comprehensive reports that examine the effects of radiation on humans indicate the atomic bomb caused no physical damage to children of survivors. According to the Biologic Effects of Ionizing Radiation (BEIR) reports, sponsored by the National Academies, data on 30,000 children of exposed atomic bomb survivors show no significant adverse genetic effects as a result of bomb exposure.

The Radiation Effects Research Foundation (RERF), located in Hiroshima, also monitors deaths and cancer in children of survivors. The RERF researchers found no increase in radiation-related disease among children of survivors, based on a health survey completed in 2006.

However, the sensitivity of genetic tests was problematic in the early years following the bombing, and some of the studies began decades later. Even now, such seemingly comprehensive findings do not provide certainty for survivors.

“This fear lasts throughout a survivor’s lifetime,” Jacobs says. “Whenever you get a fever or your kid gets sick, you wonder, is this it?”

For many years, families feared exposure to radiation would pass illnesses to their descendants, perhaps indefinitely. Even if the children of atomic bomb survivors did not inherit physical damage, the stigma of the bomb persisted for some.

“My daughter’s husband is from Tokyo. I said to my daughter, don’t say my mother is an A-bomb survivor,” Nobuko Morikawa says. “When I was young, A-bomb survivors were discriminated against with marriage and finding a job.”

///

the left) and her daughter Nobuko Morikawa (front row, second from the left) sit in the main gathering room of the World Friendship Center in Hiroshima with other translators and former volunteer director, Jo Ann Sims (front row, far left).

Recollections of the atomic bomb may seem incomprehensible to those who have not witnessed war or a nuclear disaster. Yet these are the stories that many survivors choose to share with their children and grandchildren.

The idea that families of those who endure traumatic events can share psychological damage goes by academic names such as “sequential traumatization” and “secondary traumatic stress.” This phenomenon has been observed in spouses and children of war veterans, with family members exhibiting symptoms that resemble post-traumatic stress disorder.

This concept is not uniform with all traumatic events, all survivors or all families. In a prominent meta-analysis of trauma studies conducted in 2003, researchers looked at nearly 4,500 individuals who experienced another act of large-scale violence – the Holocaust – and their children. The conclusion: no indication of shared trauma between generations.

In another survey of Holocaust survivors and their families published in July 2013, the study’s authors identified better family communication as one of the factors associated with lower levels of inherited trauma.

As part of the hibakusha legacy, younger generations are now stepping into the peace community.

Though they may be wary of the physical and psychological remnants of the bomb, many Hiroshima families understand the shared memory of each survivor’s unique experience can influence social change. As part of the hibakusha legacy, younger generations are now stepping into the peace community.

Emiko, for example, recently told her story in the U.S. as part of the Mayors for Peace nuclear disarmament campaign, and her granddaughter joined her on the trip. As Emiko watched her young granddaughter speak with the Mayor of Cincinnati, she observed the age, race and language barriers between the two as they conversed.

“We can overcome such differences,” Emiko says. “And we have to for world peace.”

Like the city of Hiroshima itself, the modern hibakusha message is one of juxtaposition: the tranquility of six rivers connected in a former hell, stories of past violence given as a present-day peace offering.

Many thanks to Michiko Yamane, Mieko Ozaki and other World Friendship Center translators.

Amanda Solliday is a freelance writer based in Yuma, Arizona and a contributor to The Riveter. She enjoys good stories, science and time spent outdoors. Follow her on Twitter @ajsolliday.