Women in Morocco turn to witches, or shawafas, for love and therapy.

article and photos by Ailsa Sachdev

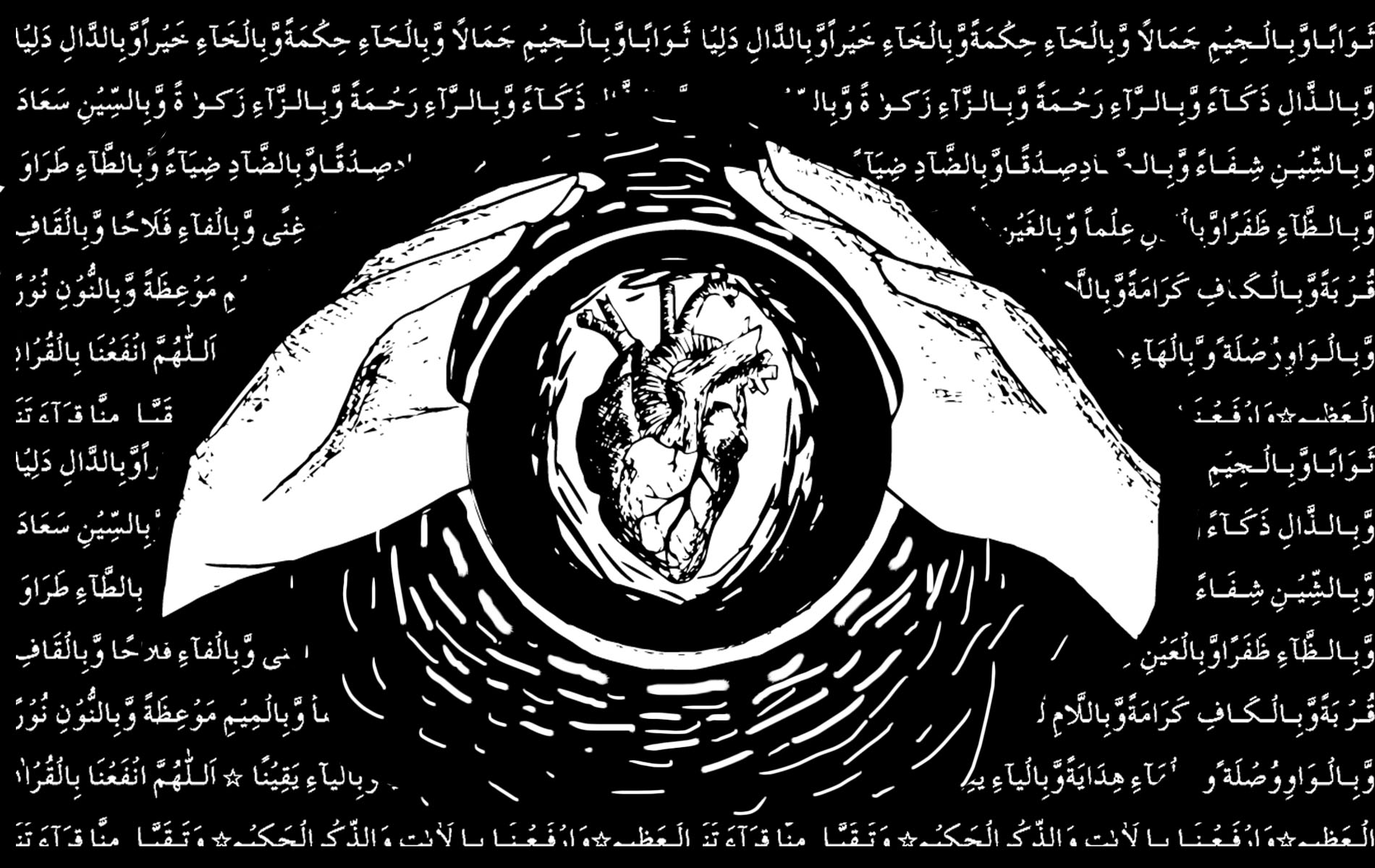

top illustration by Lora Hlavsa

The first time Salma consulted a shawafa, or witch, she went with friends on a lark, solely for entertainment. When the shawafa predicted that she would never get married, an outrageous thought for a Moroccan woman in her twenties, Salma brushed it off.

“At that time, when we left the shawafa, we laughed and we didn’t trust her,” said Salma, who didn’t believe in witchcraft or magic.

Twenty years later, the 42-year-old Salma has never married, and she has visited more than 100 shawafas in an effort to lift what she believes is a curse preventing her from getting married.

In a country where 15 percent of the population lives below the poverty line, Salma is one of many Moroccans who cannot afford counseling or mental health therapy. Instead, they turn to the mystical, seeking advice from shawafas who say they can tell the future, even though the practice of witchcraft is illegal and considered anti-Islamic in Morocco. This is because the Quran says that nobody can tell the future, except for God.

Some women ask shawafas for luck and wealth for their families. Others want to exorcise a spirit or contact a dead loved one. Most women, however, go to find love, to retain love or to forget the person they love.

In 2012, Colleen Daley, an American studying intercultural communications at the University of Pennsylvania, visited Chefchaouen, a historical Moroccan city, in search of a shawafa.

At the time, she was working for Moroccan Exchange, an organization that brings American students studying in Spain to Morocco. She was taking a group of students from the Syracuse University Lerner Center for Public Health Promotion to observe different health services, both traditional and medicinal, in Morocco.

She wandered along the cobbled streets past the sky-blue walls of the medina, or old city, asking people in her broken Arabic where she could find a shawafa.

“I heard so much about shawafas before, as evil women who do black magic, who girls will go to get a man to fall in love with,” Daley said.

But when she finally found a shawafa, Daley was surprised by how ordinary the woman looked.

“Less than a full mouth of teeth, white cloth tied on her head, pajamas stained with food from cooking, and a light cloth hastily thrown over her head at the sound of male visitors,” Daley wrote in her blog.

Daley did not want her future told, even though it was a mere 20 dirhams, or two dollars. She just sat there, quietly listening as her translator recounted the shawafa’s story about using her gift to heal people and to earn money for her daughters, ever since the death of her husband.

The shawafa “had a real light about her and a real happiness, a kind of aura,” Daley said in an interview with her. “And I’m Christian; I believe in God. I really felt the presence of God in that room at that time.”

Moroccan women turn to shawafas in times of need. Bouchra Saaidi, 32, wanted to forget her cheating ex-boyfriend. She told me her story when we met at a bar in Rabat.

In 2007, Saaidi’s cousin took her to a shawafa after Saaidi admitted to having suicidal thoughts. The shawafa predicted Saaidi’s future by studying the motion of melting lead in water. Eventually, she decided to help Saaidi forget her boyfriend. Saaidi paid the shawafa 600 dirhams, or 70 dollars, hoping that all her worries would go away. The shawafa instructed her to buy trinkets and wear a dress that would allow smoke to flow up the skirt, a practice that, shawafas say, opens up sexual energy. Then the shawafa asked her to tap her ex-boyfriend’s shoulder at noon on Friday. Saaidi was told that this action would complete the spell and afterward, she would have no more feelings for her ex-boyfriend.

As the shawafa instructed, Saaidi tapped her ex-boyfriend’s shoulder and ran away before he had the time to react. She then washed herself with water provided by the shawafa. The shawafa also used Kobol, a substance used to attract people and render them in awe of you, to bless Saaidi and to make her the woman everyone looks at when she enters a room. Saaidi then walked the main avenues of Rabat and found a new man that very day.

“One man helps you forget another,” Saaidi said. “That’s the truth of life, for me anyway.”

Though Saaidi believes in shawafas and their abilities, she also admitted that the effects could be purely psychological.

“When you go to a shawafa and she says you’re going to meet a guy in three days, it stays in your head and you keep thinking, ‘Oh I’m going to meet a guy in three days,’” Saaidi said. “It ends up affecting the reality.”

However, placebo effects, like the vitamin pill Airborne, also occur in western medicine and therapy, which makes it almost impossible to deem one better or more effective than the other. How important is the means if the ends are just as, if not more, successful?

In addition, this process can have an impact on a woman’s judgment in a society where there is a lot of pressure to get married. Women who are unable to find a husband resort to spiritual consultation to solve their problems or simply act as an emotional outlet.

How important are the means if the ends are just as, if not more, successful?

Some people go to shawafas who practice witchcraft “because they do not have money to solve their problems” through therapy, said Ali Chaabani, professor of sociology at University of Mohammed V-Aghdal in Rabat.

A single 50-minute therapy session in Rabat is approximately 300 Dirhams, or 35 dollars, which is cheaper than a lot of options in the US. However, when Saaidi went to the shawafa, it cost about 600 Dirhams or 70 dollars, to talk, have her future told, engage in a spell to forget her ex-boyfriend and eventually find a new man. If you add up the several sessions it can take to solve your problem, it actually costs less, in the long term, to go to a shawafa and fix the problem in one go. For a lot of Moroccan women, it’s a no-brainer: You visit a shawafa, pay less and have your problem solved by supernatural forces in two sessions.

Salma, whose real name is being withheld because she fears social stigma, believes that her lover’s mother, who did not want Salma to marry her son, has put a curse on Salma to prevent her from getting married. Even though shawafas have been unable to help her, Salma continues going to them.

You visit a shawafa, pay less and have your problem solved by supernatural forces in two sessions.

“If I go sad, she tells me some very nice words and I go back and I am a little happy,” Salma said. “It’s like if I go to a psychotherapy session.”

Some women in Rabat visit a marriage well that is hidden in the Oudayas Castle near the beach. Idrissi Saleh, the marriage well keeper, said the water from the well mixed with rose water changes a woman’s luck and helps in the search for a husband. Then, a woman can light a candle for the Djinn, spirits in Muslim legends, which prevent her from getting married. The women leave old underwear behind as a symbolic change in sexual fortune.

The marriage well also has a shrine dedicated to a dead saint, Sidi Abouri. Women use the saint’s tomb as an intermediary through which to ask God to change their luck, despite religious taboos.

Acts like these, including the abandoned underwear, are common occurrences in shrines dealing with fertility issues in Morocco, despite the fact that explicitly leaving something behind as sexual as underwear is often looked down upon by Morocco’s conservative society. However, since shrines are already a controversial space, these women desperately engage in this act in hopes that it will make their problems go away.

“Even though the saint is dead, it’s like he’s sleeping,” said the keeper’s son, Mohammed. “He solves all problems.”

Religion, however, is controversial for shawafas and shawafa-goers alike. Sunni Islam, the predominant sect of Islam practiced by 99.9% of Muslims in Morocco, a Muslim-majority country, forbids intermediaries between God and people – like shawafas and saints. Moreover, the Quran states that nobody but the prophet Mohammed can view the future, said Dr. Khalid Saqi, associate director of the Islamic School Dar Al Hadith Al Hassina.

“Nobody in the heavens and on earth can tell you about the unseen things except God,” Saqi said.

Under Islamic law, it is illegal to practice witchcraft in Morocco and shawafas can be heavily fined by the government under the charges of sorcery. Still, shawafas are ubiquitous in Moroccan society. Many Moroccans visit them in secret to solve personal issues. This is because some Moroccans are only Muslim by culture and don’t follow the religious laws, Chaabani said.

“A large percentage of the community is illiterate, so they don’t know what Islam says about witchcraft,” Chaabani said.

In fact, 32.9% of Moroccans are illiterate and therefore, religion is taught through word of mouth in some communities.

Despite the illegality of her craft, a 22-year-old shawafa named Miriam said that she didn’t receive trouble from the police and that she even sometimes helps male officers with their personal problems. However, shawafas’ male clients are less frequent and often come to them for assistance with issues like employment and wealth.

Miriam has no choice but to follow her craft because she believes somebody cast a spell on her when she was nine years old. Since then, Djinns have possessed her and forced her to become a practicing shawafa.

Another shawafa named Fatima also suddenly became haunted by Djinns, except she absorbed the spirits by washing her dead aunt’s clothes. I heard about her through a friend of a friend, so I decided to pay her a visit.

In Tiflet, a small town in northwestern Morocco, Fatima fiddles with the beads between her fingertips as she tells the customer her future in a secluded room located in the corner of her house. She wears bright pink pajamas concealed by a flimsy old cloth to connect with the Djinn that haunts her. Everything around her, from the tablecloth to the Islamic tapestry behind her, is green.

There is a teal lace-like fabric hanging over the entrance that you have to lift above your head to get past. Inside, the walls are white like alabaster, but almost everything else has a leafy hue. There are pine green candles and a repugnant henna concoction spread out across a table covered by a harlequin green cover, couches covered in a dim emerald cloth, green glass rose water bottles, a deep olive Islamic tapestry and other green Koranic posters.

According to Fatima, green is the favorite color of the specific Djinns that connect with her. Though witchcraft is prohibited, Fatima says she enjoys helping people. Nevertheless, Fatima and Miriam asked that their real names not be revealed because of social and legal implications of being a shawafa in Morocco.

Later, I was reading through the translator’s notes of my conversation with Fatima. I’d asked her about skeptics, of course, in which she has answered confidently: “I want them to live as I am living and live this daily suffering that I live so they understand I practice that work without my control.”

Ailsa Sachdev spent several months in Morocco on an SIT Study Abroad program and produced this story in association with Round Earth Media, a non-profit organization that mentors the next generation of international journalists. Amal Guenine contributed reporting.

Lora Hlavsa is The Riveter’s resident graphic artist. She’s a graduate of Macalester College, where she majored in geography and art, and currently lives in Minneapolis. You can follow her on Twitter@loramariehlavsa and on Instagram @coloraco.