Patsy Sims talks gutsy women and gives her top piece of advice to other women writers.

By Anna Meyer

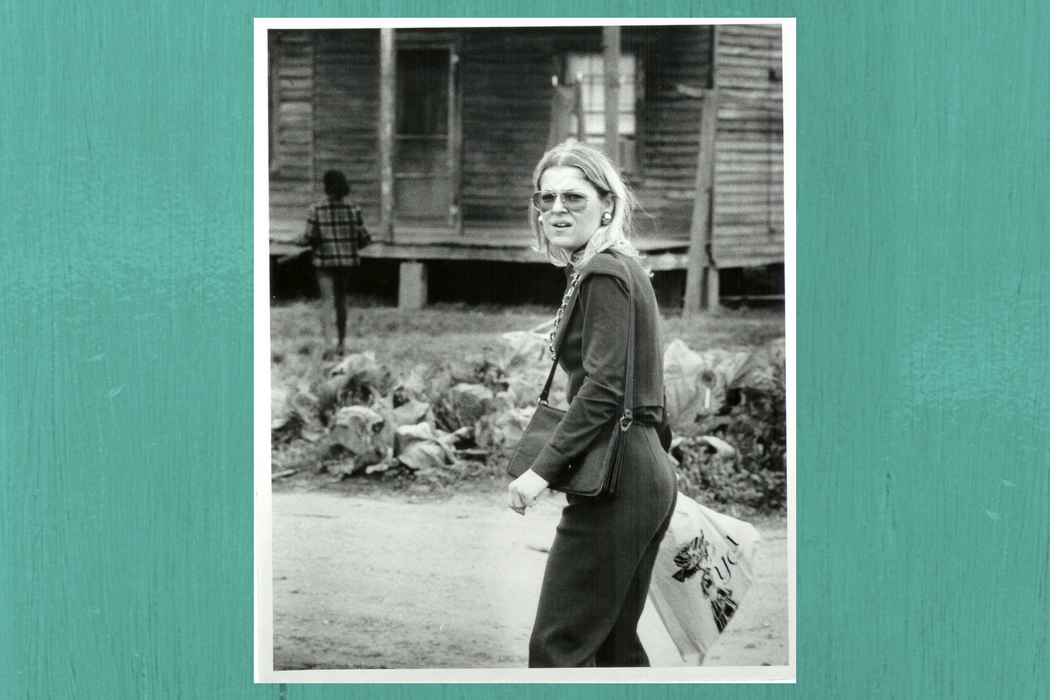

Images provided by Patsy Sims

I’m experiencing both ups and downs as a young journalist in 2017. Sure I can crowd source stories via Twitter or use Google Hangouts to instantly interview someone across the globe, but I also receive sexist messages and harassment on social media and in my inbox. Depending on the day, it can feel like this is either the best time to do this job or the worst.

Reflecting on the experiences of women journalists before me puts things into perspective. Earlier this month I had the chance to talk with the accomplished journalist Patsy Sims who began her career in the 1960s. She discussed how her experience had its own setbacks due to her gender.

“When I was engaged to my former husband, he worked for a morning paper. He went out to the fairgrounds, and he took me with him to the press box,” Sims tells me. “I mean, I wasn’t even working. I was just up there. And somebody in charge went over and pulled him aside and whispered in his ear that he needed to get me out of there. It was just this only-men zone. You just couldn’t stick your toe in the door in those days.”

This could’ve been a barrier to deter Sims as a writer, but she never saw the Press Club or other male-only spaces as something to hold her back.

“In the early 1970s, there was still this attitude. In San Francisco there was the Press Club. It was men’s only,” she says. “They would only let women come for lunch. At the time, gaucho pants were very popular. And man, I had the whole look. I had black boots, black gaucho pants and this black cape, and I’d go to the Press Club by myself with a flourish, with my cape, and thought, ‘Darn it, I’m going to have lunch here at least.’”

In her career, Sims went on to publish countless stories and three books—one of her most memorable being “The Klan,” an investigative, narrative nonfiction book that looked into the intimate lives of the Ku Klux Klan. Most recently she edited “The Stories We Tell,” an anthology of stories written by women journalists published by journalist and publisher Mike Sager. The collection features a handful of women that Sims thinks left an important legacy on what women have accomplished in this field of work, from Joan Didion to Jill Lepore to Gloria Steinem.

Speaking to someone with so much experience is humbling, but Sims had her own star-struck moments, including when she corresponded with Joan Didion. Here, Sims and I discuss her early years as a journalist, feeling like a token awards nominee and what she hopes women writers understand as they continue in their careers.

Anna Meyer: I listened to the first half of the conversation you shared with Brendon O’Meara on The Creative Nonfiction podcast, and you mentioned that it was mostly your father that inspired you to pursue writing, even giving you your first typewriter. Can you further touch on the introduction you had to writing and how you first were drawn to nonfiction in general?

Patsy Sims: Well I’ll talk a little bit about my father. From the time I was born we had what I guess you’d call a legal bookcase—you know—with the glass doors that open up and down, and before I could even read, on the bottom shelf was an encyclopedia. I remember just sitting there and opening that big book and not being able to tell at all what it was or what it said… [Laughs]. But I would be fascinated for long periods of time with an encyclopedia. That, and watching my father in his comfortable chair reading, was my introduction to books.

As a child, my maternal grandfather worked on a prison farm in Texas and ran a cotton gin. So I would spend parts of my summers on that prison farm. You got to know convicts, and it seemed like a normal childhood to me—that I had these real cops and robbers for friends. [Laughs].

The Christmas when I was five, my grandparents sent us a package with individual gifts. In that box was a present from one of the convicts who ran the prison post office, […] and for whatever reason this convict from the prison post office decided to send me a book, which I still have.

AM: I think it’s great that you’ve received encouragement and gifts because sometimes young women need that extra encouragement to break into such a male-dominated field.

PS: My mother was this real gutsy woman—not afraid of anything. So I don’t really recall thinking when I was growing up that I couldn’t do anything that a man could do, you know? It never occurred to me that I couldn’t do something that a man could do, or as well as he could.

AM: You never felt intimidated or anything?

PS: No. I didn’t. I think the intimidation came from the male editors in that they felt that I and women couldn’t [do something that a man could do]. But I guess because of whatever my mother and father instilled in me, I went on and did it. I would drive the managing editor crazy.

AM: Did you ever get into fights?

PS: He would come waving this newspaper, you know, after the first edition came out, yelling “This is not a women’s story!”

I was in the women’s section, where they always put women—well, with very few exceptions. This was in the ‘60s, which didn’t change for a long time, but that was really sort of the ghetto for women, and I think—and I don’t know, I’ve never done a study on this—I think if you go back and look at the women who became editors and in management positions on newspapers, I would guess that an awful lot of them were women who came up out of the women’s section.

But at any rate, I had started [at the New Orleans States-Item] at the beginning of my junior year of college. It was an afternoon paper. There had been a States paper and an Item paper, and they merged. And when they merged, they needed somebody back in the women’s section. So the head of the journalism program called me in and asked if I was interested in interviewing for the job. So I did.

My last two years in college, I worked there. I worked 20 hours a week after classes and then on Christmas, holidays and summers, I worked full time.

The women’s editor had a large influence on me. She was a fairly gutsy woman. She loved the kinds of stories that I did. So she let me do these stories on drug addiction and medical hypnosis and the criminally insane, and what I often tried to do to get around the managing editor was to find women [involved in the areas I wanted to write about]. Like when I was doing the story on the criminally insane, I had found a female attorney who had represented them and was very interested in the criminally insane. And so with that, I got that story in the paper.

The thing about it was that every year they had annual Press Club awards that included people from the newspapers and from stations and weekly newspapers and stuff like that, and we were winning awards that appeared in women’s sections. And at one point in the late ‘60s at the Press Club awards, I won best sports story of the year. And I knew nothing about sports. [Laughs].

I was writing a profile on a lady tennis player. That year they decided to do nominees like the Academy Awards, and I was a finalist. So there was a finalist, as I recall, from one of the TV stations, another who worked with [the Associated Press (AP)], and there was a sports editor who was this revered guy, a columnist from the afternoon paper, and me. And everybody, including me, considered me the token nomination.

Low and behold, at the banquet they call out third place, and—I don’t know—it was like the TV guy, second place was the AP guy, so then… I won. The staff of the sports department was pissed. [Laughs]. The next day at the newspaper they were just furious. It was not fair that I was considered in the sports category.

AM: And was it not fair because you were the token, or was it a level of qualification or…?

PS: Well they just thought women shouldn’t be considered for that.

AM: Ah, I see.

PS: I mean those were the days when women could not go into press boxes.

AM: So I’m guessing that as a woman you had to work harder and find ways around it because men had the full access. They had the press boxes. They had connections—

PS: Yeah, yeah. I ended up working one year on city desk, and that was a miserable year. I don’t recall doing any decent stories that year. At that point they had four, five editions of the afternoon paper, and I would have to go over every hour and check the temperature on the AP wire and give that to the city editor. That was the kind of thing that I was given to do.

And at one time, they had a bad freeze that killed a lot of the trees, and they had a “plant a tree” campaign to replace the trees. And I was given the assignment of every day writing a fundraiser thing to raise money for the trees, and I don’t remember how long this went on. It seemed to be endless. Every day I had to write a story, and every day I had to come up with a new lede about trees.

At the end of the year, [I had a chance to go back to the women’s section]. The managing editor came and called me into the office and said, “Look, you don’t have to do that. You don’t have to go back to the women’s section.” And at that point I said, “No, I’ll go back to the women’s section.” Because there, I could do the kinds of stories that I wanted to do.

AM: So at that time when you were first writing, were there any journalists that you really looked up to, admired or would model your own reporting after?

PS: Well the women’s editor did some features, but she mainly wrote this people column. And it was made up of little vignettes. I think that her interest in people and also her interest in telling little stories had a big impact on me, plus the freedom that she gave me to do what I wanted to do. I also think she was a good line editor. She taught me a lot and helped my writing out.

Later in the ‘60s—I don’t remember exactly at what point, but my father was always a big reader of the Saturday Evening Post, and somewhere along the line I discovered Joan Didion. I knew nothing about her, and I don’t think she was really known that much at that point. But that’s where I remember specifically reading the piece about Alcatraz. And I remember—and god, this is decades, you know? I can remember her description of some flowers, some little flowers, growing up through a crack in the concrete.

I’m not that much younger than Joan Didion, but I would say she was really one of the first influences on me. So those two females come to mind, and then what Truman Capote did with “In Cold Blood.” That’s when I knew I really wanted to write a narrative story, call it a nonfiction novel.

AM: Yeah, absolutely. So you later went on to write about subcultures and a book on the KKK called “The Klan” published in 1978. I mean, it’s such a daunting and intimidating group to dive into and to report on. What qualities did it require of you to do this kind of reporting?

PS: Oh, I imagine the qualities that my mother had. You know, I’m fascinated by people. I’m fascinated by what makes them tick and how they became what they are. The original publisher suggested I do a book on the history of the KKK. I said, “No, I don’t want to do a history. I want to do a story about the people. I really want to go out and meet the people and see what they’re like, why they do what they do.”

Most of the time I was never afraid. I mean, I was just so fascinated by this culture and how people could hate so strongly. How could they have such feelings?

And I have to say that I think that being a woman was often an advantage, especially with things like the KKK. And then I did another book on sugarcane plantations and the people who were working on the plantations where their families had lived on since slavery. But I think that I got to talk to people like Klansmen, and I got to talk to people that would’ve been harder for a man to talk to.

I think they also said a lot of things to me that a man might’ve not been able to get them to say. And again, for a different reason, the sugarcane workers, they had been treated so badly by society that I think they saw me as someone they could trust. They had confidence in me.

AM: Yeah! I was actually going to ask [about the advantages of being a woman], so I’m glad you brought it up. I think that it’s interesting how your sources can react differently to you depending on whether it’s gender, ethnicity, age or whatever it is. People will open up to you in different ways.

PS: Yes, and when books came out in those days, there were a lot more newspapers to do reviews. A number of the reviews of both of those books, they commented on the incredible things that people said to me. But looking back on it, it’s interesting that nobody raised the gender issue in terms of that. You know? They didn’t speculate whether or not it had to do with me being a female.

You know, at that point, I was younger. I was blonde, and I had an accent. I think [my sources] might’ve thought, “That little southern lady, that little blonde with the southern accent, what can she do?” I think they may have underestimated me. They underestimated what a female can do.

AM: Right. So when you were selecting which stories were going to be in “The Stories We Tell,” what qualities were you looking for in the stories, and what made you choose one author over the other?

PS: First, I felt that we wanted stories by women who had been leaders in the genre. I was looking both at content and style in writing because I hope that people reading it—if students read it or other writers or whatever—can pay attention to the writing and become a better writer.

There were some stories that I knew I wanted to include, like Didion. I mean, [“Some Dreamers of the Golden Dream”] is one of my favorite stories. When I was doing my Oxford Press anthology [around 2001], I used [Didion’s story]. I had done interviews with everybody in the book about talking about how they came to do the story, what was involved and different things. But I had not talked on the phone to Joan Didion. I wrote her a letter and said, “I’m interviewing everybody, and I would love to talk to you about what went into doing this story.” And I didn’t hear anything [back for a long time].

I was actually working down in Texas on a book that summer, and I got a call from back home telling me, “You have a letter here from Joan Didion. Do you want me to read it to you?” and I said, “YES!” [Laughs].

AM: Oh, what an exciting moment!

PS: So he reads me the letter, which I still have and love, and Didion writes, “Dear Ms. Sims, What you’ve asked of me is totally impossible. It’s been 30 years since I did this story. I do remember that I did this, and I talked with this person, and I went to the city hall…” And she goes into great detail about what she did, and back home they stop reading and go, “Isn’t she doing exactly what she said she couldn’t do?”

AM: I noticed that the first quote of “The Stories We Tell” is the Didion quote, “We tell ourselves stories in order to live.” Did you select that quote for the front of the book and title?

PS: Actually, [Sager] did. I think it’s a great title for the book. She’s an interesting woman. After my anthology I was going to do an on-stage interview with her in Pittsburgh, and I went out to dinner with her.

The reason why she wanted me to interview her is because she doesn’t like to do public speaking. She’s more comfortable with being interviewed. So we did that. At that point I went back and tried to read everything that she had written at that point that I could get my hands on and read it in chronological order. She’s one of my heroines.

AM: You mentioned earlier that you want readers, students, writers or whoever is picking the book up to walk away learning something new about the writing styles or the authors. Is there anything else that you’re hoping really sticks with the reader after they’ve completed the anthology?

PS: I think [Sager] and I wanted a book that would be sort of a tribute to women and for people to realize that women have done some really wonderful work. And I think I walked away feeling like: Jeez, there’s a lot more out there than I even thought there might be. There was so much. We really could’ve done an encyclopedia. But I think the primary thing was that you wanted to pay tribute to what they had done. And for people who were not aware of that, make them aware. Bring forward what women have accomplished.

I think that narratives are really important and very powerful because in the hands of a good narrative writer, you can get people to read about topics that they never would’ve thought they were interested in, simply because they were carried away with the writing.

AM: Absolutely. Is there anything else that I didn’t touch on or ask a question about that you feel is pretty important to the idea of this book or the idea of women as journalists and your inspiration?

PS: One of the wonderful things about having this kind of career and doing this kind of long saturation version of reporting is that you get to meet so many people, but also you get these mini-educations because you are getting so in depth [with the topic]. I love the research and the reporting part of it as much as the writing. It’s a wonderful way to try and make a living. You may have to supplement it with teaching and other things, but I’ve never quite understood why everybody doesn’t want to be a writer.

AM: Yeah, I’m right there with you.

PS: I look back and I think, “God, I’ve had a fabulous career.” I loved it. There’s very few things, I mean—I didn’t like doing the temperature back in the day, and there was this one year where I had to work for the state board of health writing news releases and things, and at one point I had to write a brochure on rabies, and I remember, being the narrative writer then, I wrote it from the point of view of the dog. [Laughs].

AM: You found a way to make it what you wanted.

PS: You know I’m sure that those days aren’t over. But my advice to women is just to keep finding a way, and look for a way around the hurdles.

Note: The interview has been edited for clarity and length. This is an updated version of the interview that was previously published in our newsletter on November 28, 2017.

Anna Meyer is The Riveter’s Digital Editor and a Minneapolis native currently calling Norwich, England home. She spends most of her funds on concert tickets, traveling the world, and doing all things fueled by her daily espresso. Her work has also appeared in Shine Text and Inc. magazine. You can stay updated with her work via her personal website.