The real numbers behind the experiences of women in science writing.

by Karen Hess and Aparna Vidyasagar

Journalism has a problem.

Its women are disappearing. In the academic world of journalism, women abound. In fact, at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, women make up roughly 71 percent of all undergraduate and professional master’s degree students.

We are both studying science journalism at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. In our classrooms, we’re surrounded by women. We don’t lack role models, either; we have many respected female professors. However, somewhere between graduation and getting published, landing professional jobs or winning awards, these numbers dwindle. For example, The Women’s Media Center reported that on average, women wrote 37 percent of the articles at the nation’s 10 largest newspapers. They also reported that men have outnumbered women in newspaper newsrooms since 1999.

The vanishing act happens over time. A 2013 study by the School of Journalism at Indiana University found that as years of work experience increase, the percentage of female journalists decreases. Of the journalists surveyed, women made up nearly half of those with up to four years of experience. Those numbers tapered off until women made up only 33 percent of those with twenty or more years of experience.

Such disparities in numbers are also reflected in sub-specialties of journalism. The Women’s Media Center found that men more frequently report on topics such as world politics, business, technology and science. Since its inception in 1988, no female author has won the prestigious Royal Society Winton Prize for Science Books.

It’s not a new phenomenon, but recently, female science writers have been speaking about their experiences. Just search #RipplesOfDoubt on Twitter to read some of their stories of harassment, experiences with gender bias and being on the receiving end of behavior that’s hard to define, but makes one feel less than worthy. Most of these experiences happened on the job.

Earlier this year, around 90 science writers came together to address some of these issues at Women in Science Writing: Solutions Summit 2014 held on the MIT campus June 13-15. This group discussed unequal opportunities, gender bias and harassment. They also collectively brainstormed solutions to these problems.

Prior to the conference, we were asked to coordinate a survey to understand experiences with these topics. One of the primary goals of the survey was to gather data representative of the diverse science writing community. Some are trained journalists, others are scientists, while still others write for the love the craft. Some work as reporters, or as bloggers, freelancers or public information officers. We worked with the conference organizers to reach out to science writers through various professional organizations and on Twitter. A panel of leading science writers presented the results at the conference.

As a result, for the first time, we had real numbers to support the extent of gender issues in the science writing community.

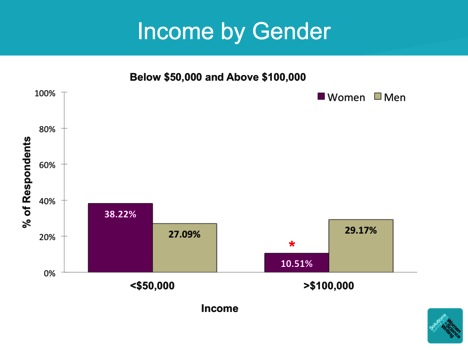

Who makes the most money?

According to our data, it’s men. While around 29 percent of men earned $100,000 or more, only about 11 percent of women were in that earning bracket.

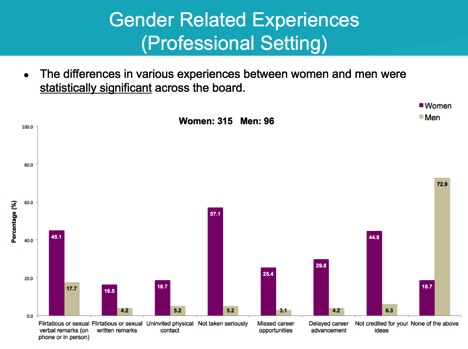

When a woman speaks, is she heard?

From the data we gathered, the answer looks like ‘no’. About 57 percent of women who took the survey said they weren’t taken seriously in a professional setting. Moreover, about 44 percent said they were not credited for their ideas.

These are just a couple of examples of the types of behavior women said they had encountered as science writers. They had been flirted with, and had dealt with uninvited physical contact. But also, they said that because of their gender, they had missed career opportunities, or had been delayed in moving up the ranks.

As for the men, nearly 73 percent said they hadn’t experienced any of this.

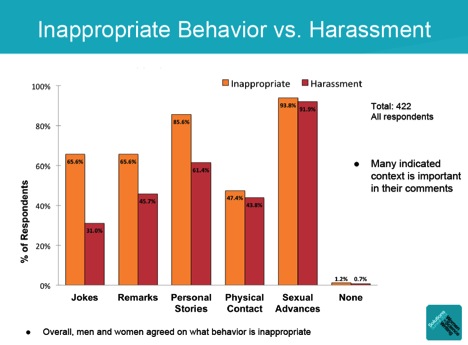

Can we define harassment?

Not exactly. Those who took the survey saw the same list of behaviors twice–first, to decide if they were harassment and again to decide if they were inappropriate. Overall, men and women easily agreed on what types of behavior were inappropriate–sexual advances and stories with sexual details and references, for example. But, overwhelmingly, in write-in comments, the respondents made it clear that the definition of harassment was in the details. Who does it, how often it happens, and where it happens all make a difference.

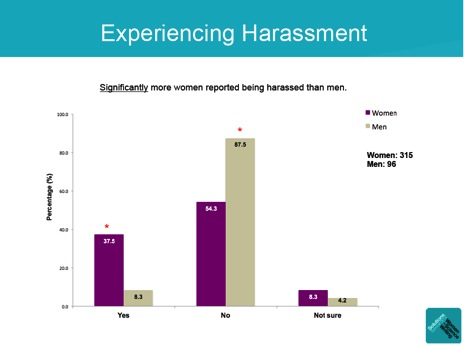

When it comes to harassment, what’s the difference between men and women?

Nearly 38 percent of women said they had been harassed as compared to 8 percent of men. While women mostly said they were harassed by men, men said they were mostly harassed by women.

Overall, the data was confirming for many and let them know they weren’t alone Many of the reactions were expressed via the conference Twitter handle (@SciWriSummit) and hashtag (#sciwrisum14).

So, where do we go from here?

Science writers are working together to initiate change. The conversations and deliberations that took place during the Solutions Summit led to the development of the Freelancers Bill of Rights. The bill was built off of data from the survey and information from breakout sessions that took place during the conference. The document consists of pledges to create a fair work environment, equal opportunities and a work experience free of harassment. With the support of editors at various publications, the bill can become a well-rooted reality.

Inequality, disrespect, biases or harassment shouldn’t be part of our futures when we step into the world of career journalism. Nor should these attitudes linger for those who come after us. This conference was the first step toward a solution, but more work needs to be done.

Hopefully, someday, women in journalism will stop disappearing over time.

See all of the slides from the conference here.

[hr style=”striped”]

Karen Hess is a graduate student living in Madison, Wis. She writes about science, health, and the environment. Follow her on Twitter @Karen_Hess.

Aparna Vidyasagar is a graduate student in journalism and lives in Madison, Wis. She enjoys writing about health, life-sciences and disease research. Follow her on Twitter @aparnavid.