A journalist remembers questioning murder victim Susan Berman’s best friend.

by Jax Jacobsen

HBO is halfway through “The Jinx,” its six-part documentary series of interviews with Robert Durst, the posh real estate mogul who may or may not have killed several people, and others who can possibly shed light on his activities. His ability to escape prosecution has captivated audiences for decades.

Durst was questioned, but never charged, in the killing of his first wife, Kathleen Durst, who disappeared in 1982 after she filed divorce proceedings. The mogul was also tried – and acquitted – for the murder of Morris Black, his 71-year-old neighbor in Texas who was killed and decapitated in 2001.

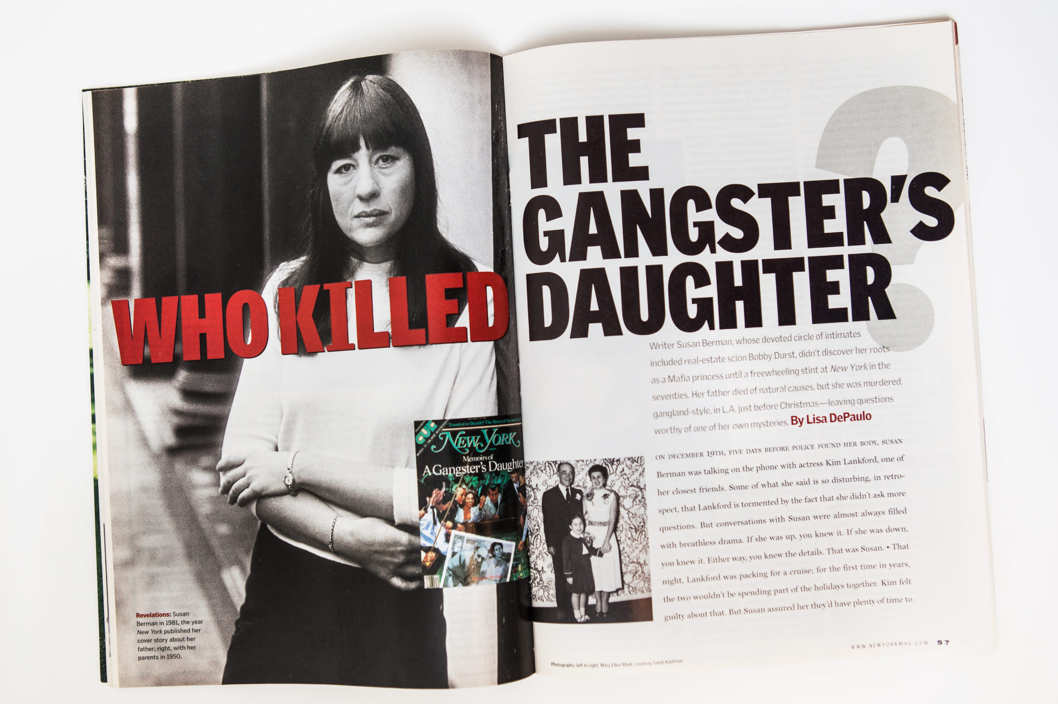

Last Sunday’s episode focused on his friendship with writer Susan Berman, the famed journalist and author who was shot execution-style in her Beverly Hills home in 2000, just weeks after the Kathleen Durst case was re-opened and law enforcement was looking at Durst as a person of interest. At the time of Kathleen’s disappearance, no charges were ever laid and investigators didn’t even search the Durst home.

After his wife’s disappearance, Durst relied on his friend Berman as his spokesperson to the media. Berman’s money troubles were brought to light, raising the possibility that Berman may have told Durst she would reveal something about Durst’s involvement in his wife’s disappearance if he didn’t give her more money. Durst emphatically insists he had nothing to do with Berman’s death.

Despite the focus on Durst and his eccentricities, the mention of Susan Berman brought me back to my college journalism class in 2002, where my journalism professor, Hillary Johnson, tried to teach us how to interview subjects about emotionally sensitive topics.

It would turn out to be one of the most uncomfortable nights of my undergraduate life.

We were sitting in a windowless classroom in a campus building at Marist College, located halfway between Manhattan and Albany, New York, absorbing tips from my professor, a seasoned journalist, on how to interview sources and glean critical information from people who may have just witnessed or experienced traumatic events first-hand.

Lectures are one thing. Actually putting someone through the drill, my instructor knew, was quite another. And so she volunteered to be our first test subject. “Interview me,” she said, “about the murder of my best friend.”

That best friend was Susan Berman.

The questions came hesitatingly at first. This wasn’t the standard unwillingness of students to participate, but a recognition that what would come after would be very hard to hear.

We started with softballs: “How did you meet her?” “How did Berman know Durst?” “Where were you when you learned she was killed?”

Professor Johnson was visibly annoyed. “Those aren’t hard questions,” she said. “Ask the gut-punching ones.”

So we asked for the gruesome specifics. We pummeled the professor with a barrage of questions about how Berman was gunned down in her bedroom, of the way her body looked when it was found on the floor. We asked if the professor had viewed the crime scene photos, and if Berman could have had any inclination that she was about to be murdered.

The questions came faster and faster, and we rode the sick swell of enthusiasm, excavating the most awful and lurid details of this woman’s death. It took me an embarrassing amount of time to notice that our professor, though still answering our hateful, inconsiderate questions, had started to weep. Hateful, because we didn’t care, in the end, about the assignment or Berman or Durst, and it showed. We had taken a quick detour to reveling in the sensationalized high of taking advantage of our position – journalists-in-training, sure, but still journalists.

Years later, watching “The Jinx,” I’m struck by two things: how easily journalists lose track of their sense of compassion in order to get to the most sensational parts of the story, and how baffling it is that we, in the end, fixate over the alleged killer with little to no memory of the victims or those who were close to the people allegedly slain.

We’ve done it again and again – from Charles Manson to the “Killer Clown” John Wayne Gacy to the more recent examples of Colorado movie-house killer James Holmes, Sandy Hook murderer Adam Lanza, and the killings of six people by UC-Santa Barbara student Elliot Rodger.

We’re well versed in the psychotic quirks of these individuals – but how much do we ever know of the victims? It’s the personalities of the killers that we’re most interested in, to the point that it nearly obscures what we think they’ve done or what they’ve been confirmed of doing.

Perhaps—in this case—the fascination is warranted, because only Durst knows the extent of his involvement with the women’s deaths.

But in the end, these unsolved murders disappear from view. Though we start out empathizing for the victims, our attention shifts to Durst’s personality tics, his privileged lifestyle, and his “talent” for eluding justice. I’ll stay tuned to “The Jinx,” but keep the lesson I learned that day in mind.

[hr style=”striped”]

Jax Jacobsen is a Montreal-based journalist who has written for the Montreal Gazette, The Guardian (UK), Geopolitical Monitor, and elsewhere. Follow her on Twitter @jaxjacobsen. Her work can be found at www.jaxjacobsen.com.