Grammy-winning Justin Vernon recorded For Emma, Forever Ago in a Wisconsin cabin in 2007. He released it as Bon Iver just ten days after the first iPhone went on sale. An Eau Claire, WI native explores why that feels like forever ago.

by Kinzy Janssen

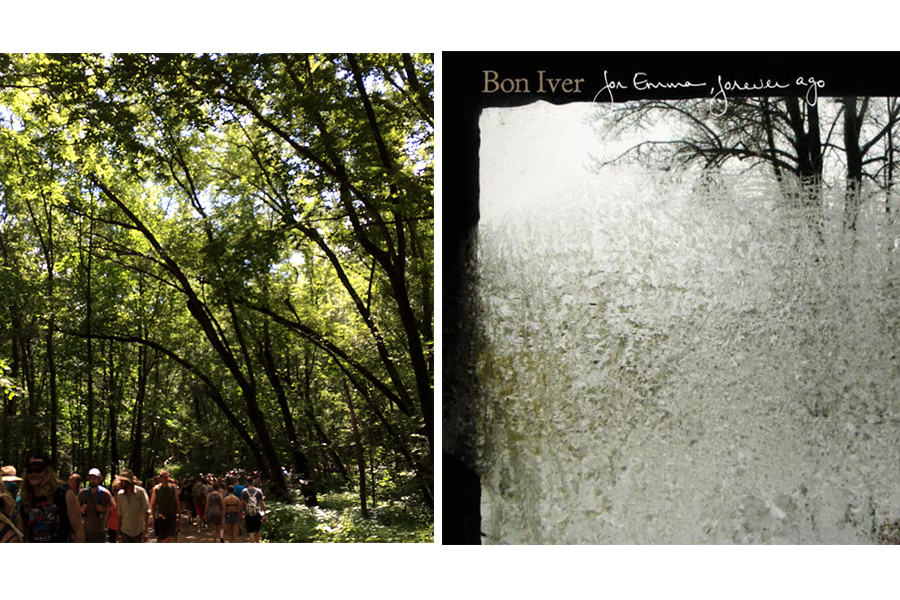

photo by Kinzy Janssen / album art courtesy of Rolling Stone

On July 8 2007, the first icy notes of Bon Iver’s self-released For Emma, Forever Ago were just reaching the Internet. Ten days earlier, a much bigger wave broke on our collective shore when Apple released the world’s first smartphone. Though underestimated at the time, the iPhone’s influence would become tsunami-sized, revolutionizing our society within just a few years.

If you don’t yet know the origin story of Justin Vernon’s Bon Iver, or haven’t heard his music, know that they are indivisible: Man goes into a hunting cabin in the woods of northern Wisconsin. Man chops wood and writes music. Man records best-selling album, without intending to. Man emerges, blinking in the sunlight, to applause and rave reviews.

I don’t think it’s a coincidence that Vernon’s hibernation story has retained its mythical quality eight years after For Emma. Since then, smartphone usage has ballooned: by April of this year, 64 percent of Americans owned a smartphone, and a quarter of the world is expected to have one by 2016. The devices have dazzled us and entertained us and even saved our lives, but they’ve also ushered in a host of heretofore unnamed problems, from text neck to technoference. To me, Bon Iver’s recuperative wood-splitting venture marked the end of an era, an era when people could wander into the woods without having to decide whether to take iPhone along.

Mentions of Vernon’s lumberjacking episode did not subside in 2011 when the musician released his second album, Bon Iver, Bon Iver. Neither did it lose relevance when he won two Grammys in 2012, one for Best New Artist and one for Best Alternative Music Album. Headlines couldn’t resist illustrating the unlikely arc: “From A Log Cabin To The Grammys.” Now, music magazines are still wringing the last drops out of the narrative. As the story recedes further into the past, it acquires the aged patina of a myth: the details change depending on who tells the story. Some say he retreated for three months, some say four. Austin City Limits assumes he wrote For Emma in the mountains (a claim I can definitely refute, having been to Dunn County, WI).

Bon Iver’s story is compelling and true, though parts of it sound exaggerated to me because I am familiar with the environment in which he wrote For Emma. I grew up in Eau Claire, WI (population 65,000) and attended the same high school as Justin Vernon, though not at the same time — we graduated five years apart. I still smile smugly when I hear the words “wilderness” and “isolation” applied to Vernon’s father’s hunting cabin. “That’s not wilderness,” I want to say. “That’s just one county over.” Likewise, Vernon’s recording studio in Fall Creek, WI, where he’s lived since 2008, is described as “remote.” To some it may be, but to me it was always just an 18-minute drive through wooded hills east of town.

Still, no matter how much time passes, I find myself being swept into this modern-day Henry David Thoreau narrative. (Thoreau’s cabin on Walden Pond, incidentally, is a mere two miles away from the bustling town of Concord, MA). Maybe it’s because the experience already feels bygone, sepia-tinged, and impossible to recreate. Maybe it’s because pre-smartphone 2007 feels like another age, even though it’s only been eight years.

And yet it seems Vernon is trying to duplicate the conditions that spawned his creative awakening (minus the loneliness and liver infection), for bands he admires. Last winter, he invited The Staves, a trio of harmonizing folk-rockers and sisters from England, to spread out, clear their minds, and shape their first album at April Base, his recording studio/home in Fall Creek.

“To have this space, to be surrounded by this kind of nothing, and a load of trees, has been really freeing,” says one of the sisters in this mini-documentary about the experience. The camera closes in on a frost-laced window (a direct echo of For Emma’s album art) and the sisters, wrapped to their noses in scarves, huddle together for warmth.

The Staves refer to the song maturation process at April Base as “honest” and “natural” and they call the place “magical.” Though the musicians are surrounded by equipment and high-tech mixers, they seem to regard the place as a catalyst for human connection and purification. At the end of the documentary, a series of Polaroids show the crew laughing and embracing. Vernon expresses sadness that the experience is already shrinking in the rearview mirror. Throughout the short film, winter is portrayed as “authentic.” Why? Maybe it’s due to the marriage of physical and emotional exertion — what we share by stacking logs or stacking harmonies — and the simplicity of the breath that drives them both.

Justin Vernon was “unplugging” before we knew that unfiltered interactions with people and nature were in jeopardy.

THE TIPPING POINT: EVEN TEENS WANT TO UNPLUG

The magnetism of the cabin story and of April Base remind me of the rationale behind smartphone addiction camps such as Camp Grounded and Digital Detox, which have proliferated in response to screen addiction — that constant compulsion to check, scroll, swipe and post. Camp Grounded attendees, who are adults ranging in age from 19 to 67, praise the ability to create real, one-on-one connections with people by stripping work titles, gazing up at the stars, and indulging in “cuddle puddles,” according to a July 2013 New York Times article. When they first arrive, participants feel tethered to their absent phones. One woman describes feeling the “phantom buzzing,” the tingle “like a missing limb.”

“There’s always going to be more media, more to do outside of where you are,” said Digital Detox co-founder Levi Felix in the same article. “I think that when you create a space of authenticity and openness, there’s true, true respect.”

It seems we’ve reached a tipping point. In fewer than eight years, we’ve see-sawed from fascination to disgust over these intervening screens. Now, as we look inward, many crave a return to a pre-digital era. To this end, we set limits for children and draw lines for ourselves. In a 2013 teen summer camp experiment, phones were confiscated during the first week and then returned to campers for the second. The minute the teens had access to Snapchat and Instagram again, they became walled off. But slowly, the teens started to realize they preferred Week One—and that they actually looked forward to milking goats more than mindless texting with friends back home. One girl even handed her phone back to the counselor.

Even those of us who don’t “do” camping seem to want to connect with nature more than ever, if only vicariously. In 2014, there were 20 different reality TV shows or documentaries being filmed simultaneously in Alaska, our most remote state. One show is aptly named “The Last Frontier” (also the state’s nickname). From our living rooms, we can stare down a bear, too — or accompany a man delivering fuel to a neighbor who would die without it. There is life, and risk, beyond our smartphone screens.

EAUX CLAIRES: TREEPTOP DETOX

Last weekend, I drove an hour and a half east to my hometown with a college friend for an entirely Bon Iver-curated music festival called Eaux Claires (the original French spelling of the city). We hiked down the sandy, pine-anchored paths to the festival site overlooking the Chippewa River alongside 22,000 other people — a third of the population of Eau Claire. Treetops provided a grandiose backdrop to the main stages, and a third stage was situated at the end of a steep, winding trail through the woods. On both nights of the festival, the leaves were lit eerily from below, and four-paned window-frames hung suspended in the trees. “I’m going to try to use my phone as little as possible,” whispered my friend. But it wasn’t just her. “People weren’t here to take selfies,” wrote one attendee on his blog afterward.

Make no mistake, Eaux Claires was a thoroughly modern festival. There was an Eaux Claires app that contained concert schedules and optional push notifications. And yet, it seemed people were more attached to the “field guides” we grabbed while passing through the entrance, above which hung a billowing yarn installation by HOTTEA — the Minneapolis-based “yarnbomber.” The 3-by-5-inch yellow-bound booklet displayed information about the local flora and fauna, and identified the current moon phase (waxing crescent) and sun position (daylength: 15:10:04). The phrase “this place” was repeated like a heartbeat throughout descriptions of our logging past, our Ojibwe/Hmong/Scandinavian heritages, polka, and pines. The overt tribute to “this place” was what made it feel personal, even for those who don’t claim Eau Claire as their home.

Concert-goers paged through and read passages to each other aloud, including the prose poems that served as band descriptions. The blank pages in the back urged people to “Scrawl, y’all” and my friend used that space to sketch people resting in the shade. The booklet even contained a tongue-in-cheek invitation to owners of “futuristic smart telephones” to download the app, but it’s clear why people preferred the field guide — because it would serve as an artifact of a particular time and place when compared to the no-longer-useful app.

It’s not that we were meant to “unplug” at the festival, per se. There were phone charging stations, and tweets bearing the #EauxClaires hashtag posted during and after the festival. But I saw very few phones wielded in the air, especially when Bon Iver played the finale, the band’s first performance in three years.

Sufjan Stevens, who performed at dusk just before Bon Iver, confessed that he usually doesn’t book festivals due to his agoraphobia (fear of large crowds), but that he made an exception for Eaux Claires because of its intimate, everyone-knows-everyone vibe (most of the musicians were connected to or friends with Justin Vernon). Later, as I stood 10 rows back from the stage, waiting for Bon Iver, I chatted with a couple from San Diego who opened up to me about the beauty of Eau Claire: “We expected it to be beautiful, but we didn’t expect to fall in love with it so much,” they said. “It’s so green; so lush!” For the rest of the concert countdown, we talked about land formations and weather. I learned they were en route to Detroit — they were moving there — so I gave them cold weather tips. He talked about looking forward to the being snowed in so he could focus on his photography.

When festival narrator Michael Perry (an acclaimed author who lives nearby) introduced Justin Vernon on his hometown stage, he asked us to think about the confluence of two rivers — one of the defining geographical characteristics of Eau Claire — and about our “confluence of 22,000 beating hearts.” He asked us to “feel the river.” A little sentimental? Sure. But we felt it. One guy listened to the entire set while lying in the grass and looking at the stars. Justin Vernon made a case for friendship being “the best thing we can all count on.” When the concert ended, we emerged blinking, as if at the end of a long winter.

After the festival, an acquaintance of mine who teaches English in Eau Claire wrote about his need to “seek confirmation” of the festival’s effect. I know exactly what he means. Why had tears sprung from the corners of my eyes at the moment when “Perth” built up to its deluge? Was it because I could feel the pounding and the brightness in my chest? Was I crying because this was my favorite band? Or was it the pride of being surrounded by so many people absorbing the often-unsung decadence of a Wisconsin summer?

Maybe it’s because I recognized in everyone a willingness — a fierce desire to forge connections despite the distractions we carry around with us every day. We don’t want Retina Display to replace what our retinas display. And as long as that desire exists, we’ll be okay. We’ll find ways to draw lines and leave our devices behind. We won’t let our humanity melt into a touchscreen display.

[hr style=”striped”]

Kinzy Janssen is a 2014/2015 winner of the Loft Literary Center’s Mentor Series in creative nonfiction. Her poems and essays have been published by JMWW, Innisfree Poetry Journal, and the Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts and Letters. A serial Midwesterner, Kinzy grew up in Wisconsin, earned an English degree from the University of Iowa, and now serves as Copy Editor of The Riveter in Minnesota.